a day out

It’s a chilly morning, around 7 degrees, more of a stay in the bed type of morning. For Paulin Coutelas, it could be freezing or boiling, it really doesn't matter. Today is the 28th of April 1941, it's a good day because Paulin is going out of the Aincourt internment center.

1 year earlier, in the summer of 1940, France had lost the Second World War against Germany. It was a complete debacle, a humiliation to a level barely imaginable.

Paulin didn't see much of the war, it was quite the surprise for him when he heard that the french were being beaten, it was quite the surprise for everyone.

The french were supposed to be the best army, so Paulin was told. He was only 8 years old during the First World War, but he remembered great stories of the french army, holding on, never giving up, always resisting.

What happened then?

What happened then?

When France and the United Kingdom declared war to Germany on the 3rd of September 1939 after the invasion of Poland, Paulin wasn't called to fight as a soldier, he was ordered to stay at his job, as a carpenter for the national train line, the newly named SNCF. So he worked, one month passed, then 2, 4, 6 months, doing his old same job, this time as a "special affectation". Nothing was different, nothing changed, the same work all day long, the same trip back home every evening.

He didn't know his army was losing the war, this wasn't the type of information you would hear. He heard the german attacked, but the french army fought bravely. He heard Belgium might have been occupied but that the french army was still standing. He read that the french and british army were circled around Dunkerque and Calais, this was hard to believe. On the first day of June, Paulin was even told that Lille, a city in the north of France, was occupied too.

On the 3rd of June, german planes flew near Paris, it sure wasn't a good sign. That was the beginning of the end.

2 weeks of chaos followed, crowds leaving Paris, the german troops entering the capital without resistance, the government escaping, it was such a mess. And Paulin was still at his work, confused.

On the 17th of June, the marshal Petain, the new head of government, after Paul Reynaud’s resignation the night before, called for a cease fire. The war was lost, Paulin came back home earlier to his wife Helene. They talked all night, trying to make sense of the events. Can Germany win the war against the best army in the world? Where is the french army? What happened?

Helene too was confused about the whole situation, but she was mostly relieved. Paulin wasn't called to fight as a soldier, he stayed close to her, at his job, he didn't have to fight, to kill, to get hurt.

And Paulin went back to work, the same job, no more special affectation, still the same job.

What then? What happens when an entire country loses a war? Was the country now part of Germany? Was it occupied? Was there still a french government or was it now german ruled?

Neither of those things happened. France was occupied but only half of it, the north side and the west coast. France was still ruled by a french government, but there was now a good relationship, a partnership even with Germany. A collaboration. There was still a war, a World War, but France changed side. France cave in, France gave up.

Back in the present, in 1941, Paulin is getting out of Aincourt, a sanatorium converted into an internment camp. He first leaves the youth area. Everyone there is in their twenties, except for Paulin, already in his thirties. They all want to fight, to escape, to resist in a way or another, but Paulin wants to see his wife. So he kept quiet, he didn't raise his voice, he didn't participate. And today, he is rewarded, he's getting out. He moves to the entrance, he is given his old clothes, he passes the guards, the machine guns, and there he is, out of Aincourt.

The sun is on his back, and he can see his shadow on the ground. There's also a second shadow, a shadow wearing a police uniform.

In 1940, Paulin wasn't quiet. He didn't appreciate the german troops near his home at Rosny-Sous-Bois, or at work. He didn't like the fact that the hour changed at Berlin time, he certainly wasn't up for his work helping the german army in any shape or form. He would not help fascism.

He wanted to shout at every corner of every road that he didn't believe the war was over, despite the Vichy regime claiming it. So he started to think as he used to a couple of years before, when together with some fellows co workers from the communist party and other syndicates, they took it to the streets, and fought for their rights, for paid holidays, for 40 hours a week instead of 45.

Strikes, pamphlets, reunions, there are many ways to resist, to speak your mind. During breaks, Paulin started talking to his co-workers, to assemble committees, to speak from one strong voice rather than a multitude of quieter ones.

It was hard, the german victory against France was so brutal, most people in France had very little optimism, it felt that Germany was much stronger, unstoppable that there was no turning back anymore. They were polite too, they didn't sack the entire country, they smiled, sometimes they helped you carry your luggages. Very few of his co-workers agreed with Paulin, very few agreed with someone too close to the communist party.

It's not that Helene disagreed, but she was worried about Paulin. Maybe he was being too vocal about his opinion. Sure, his voice mattered back in 1936 during the massive strikes, yet this was different, this was about the german troops, this might get dangerous. And Helene was pregnant with their first child.

Paulin couldn't be happier about the news. Parents, they will become parents! Everything was different now, Paulin wanted to do anything for Helene, to help her in any way. A baby is a great change in a family.

The Vichy regime wanted to maintain order, and the communists were an issue, even to previous governments. Accused to be anti France, against the war, on the german side, to influence the soldiers to stop fighting and to throw the country into defeat, the marshall Petain was also worried of the communist propaganda and wished to get rid of the problem for good. Forbidding the communist party wasn't enough, forbidding all communst print wasn't either, now the communists needed to be taken away, they needed to be detained. The most dangerous elements, the most actives were to be arrested, yet since the declaration of war and the occupation, the list of the communists elements were not up to date, some were written as dangerous for participating to strikes back in the thirties, some were only on those lists because they subscribed to the coppubist party. It didn't seem to matter, to Vichy's eyes, any communist was a dangerous one.

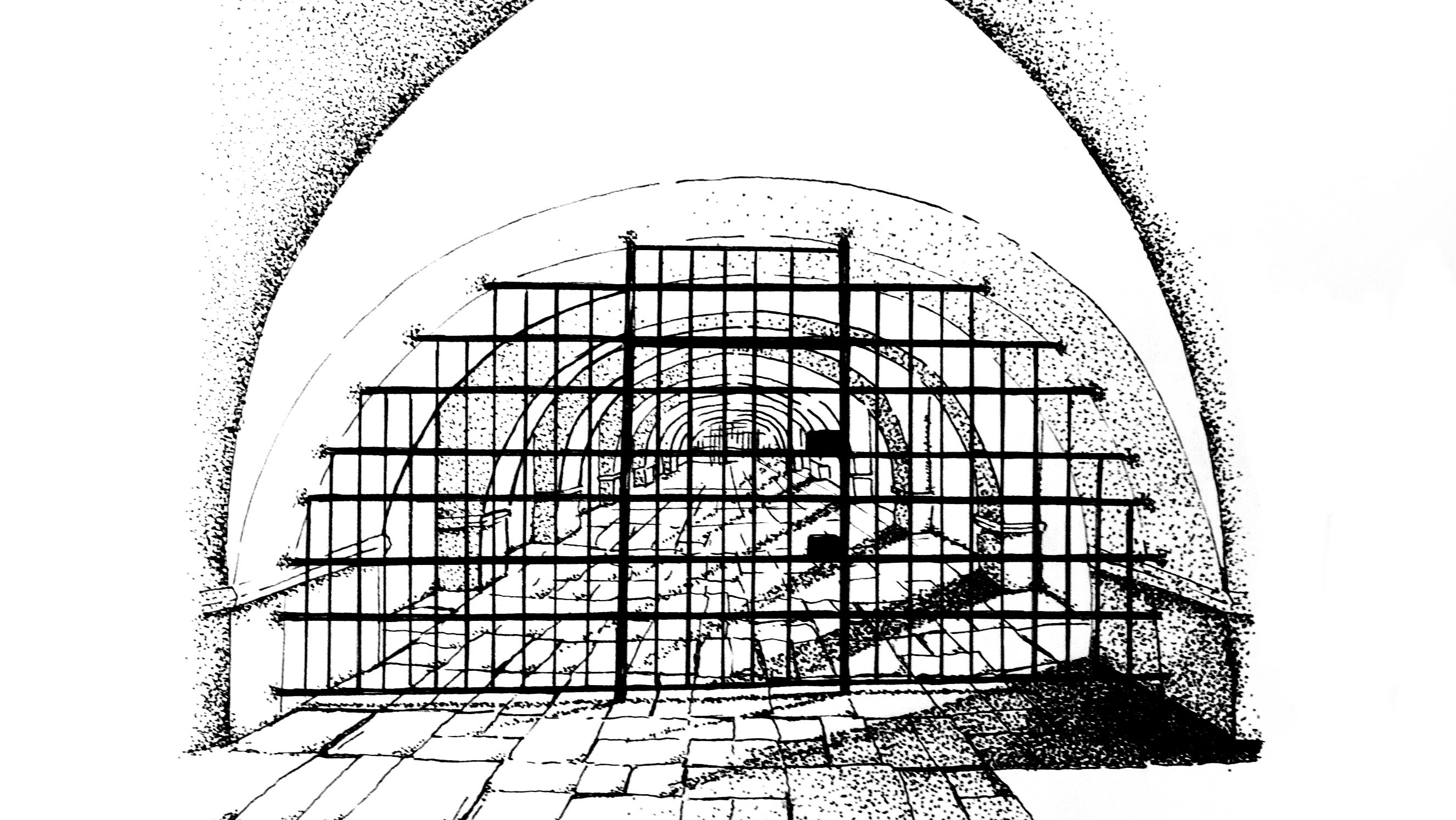

The Aincourt Sanatorium, previously a center for tuberculosis patients evacuated in june 1940, seemed ideal for a reconversion as an internment camp, or a stay center under surveillance, so as not to sound suspicious. The camp became the first of its kind in France, the first internment camp in the occupied zone, run by the Vichy regime. Right in the middle of a forest, 70 kilometers away from Paris, close to a train station yet not so easily accessible for the prisoners, families, Aincourt had many qualities for the authorities, and it truly didn't matter if the prisoners felt isolated, crammed to a point where they were confined in a canteen converted into a sleeping area..

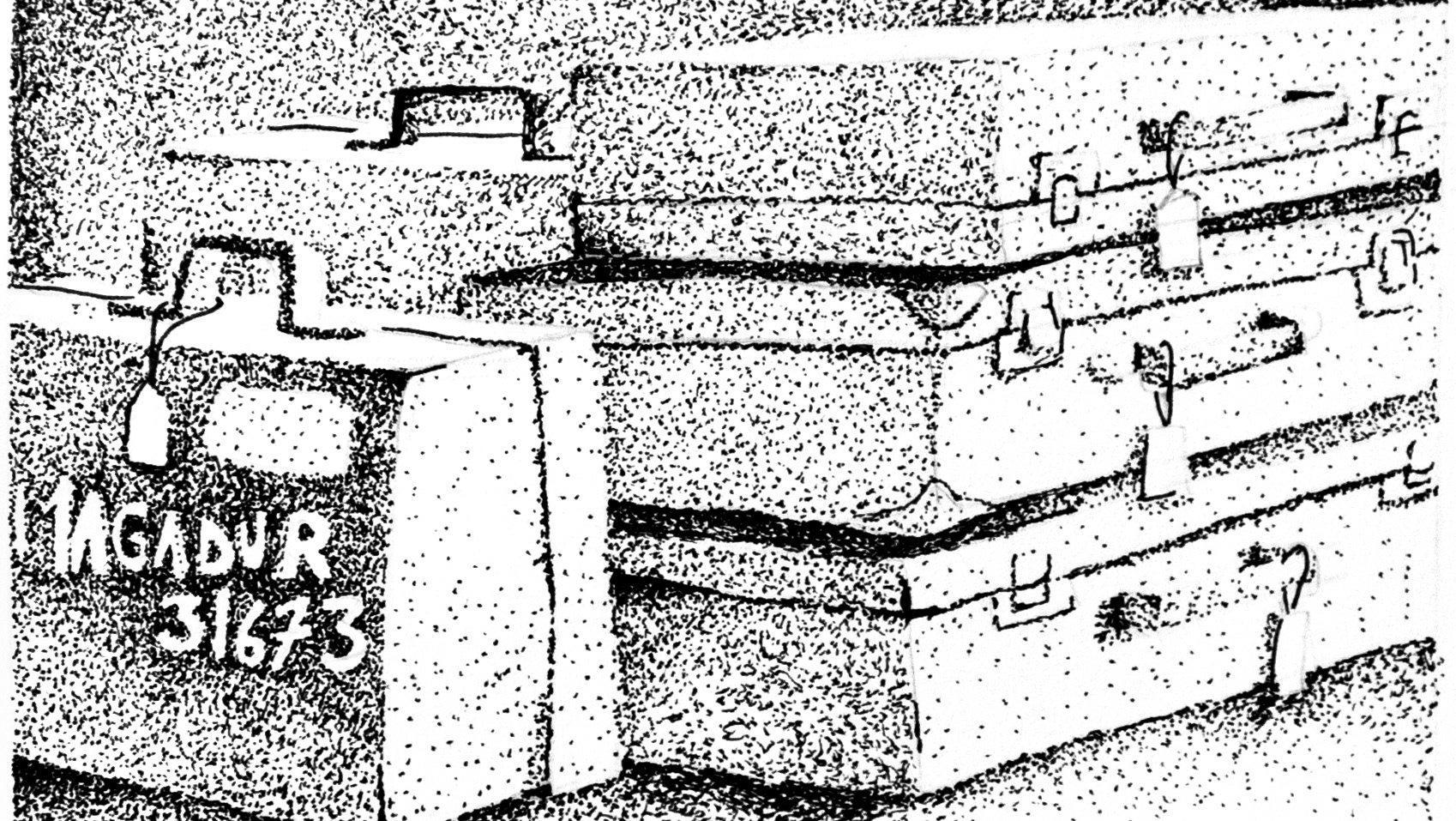

On the 26th of Octobre 1940, Paulin was arrested, as a consequence of the 18th of september decree, stating that anyone presenting a danger for the nation could be arrested and jailed indefinitely. Paulin was communist, he also had been reported by someone at his work for speaking his mind, and like 40 people that day, he was arrested and sent to the Aincourt center. No evidence was necessary, no trial, no sentence, no appeal, he was just arrested and brought to Aincourt… detained… under surveillance… indefinitely.

Indefinitely.

Now, back to the present, Paulin is out of Aincourt, taking a train from Mantes to his hometown, Rosny-Sous-Bois. He behaved for the last 6 months, not one word about Germany, about France, about anything really. Paulin is about to meet his daughter, Claudie, who was born on the 22nd of March. Helene was so brave, she was all alone, pregnant, without Paulin, without work, doing her best. She sent letters to the local prefect and all thanks to her, Paulin came out of Aincourt, he was finally free…for one single day.

Free for one day, one day to get his clothes, to get out of Aincourt, to take a train from Mantes to Rosny-Sous-Bois, then to see his wife, to meet his daughter, and finally to leave around 6.30 and make the journey back to Aincourt. 6 months of good behaviour, of promises to never be part of the communist party, to say nothing about France or Germany, 6 months of letters from Helene to the prefect, begging for her husband to come back at his old job and help the family. His reward for all that was one day.

But today is still a good day. It may be chilly, but his heart is already warm. Helene is at the station, waiting for him. Claudie is here too, in a small wooden stroller. Finally, they meet.

They have so much to talk about. Is claudie feeling well? Does she eat enough, with all the rationing in France? How is Helene, is she not depriving herself of food so Claudie has enough? Paulin needs to thank Helene's parents for all their help, his parents too, and his brothers, of course, Gustave and Isidore. Paulin is not sure he'll have enough time.

Helene is so happy, yet she can't help contain her anger, as she realises that Paulin is not alone, there is a shadow in uniform next to him, and the shadow is staying.

They spend time, they talk about anything but politics, or war. The shadow is listening. It doesn't matter, there is so much more to talk about.

Paulin and Helene kiss in front of the shadow, they care about Claudie in front of the shadow, they eat with the shadow. This is what it feels like during the Second World war in France, you live with a shadow listening to you, watching you, spying on your intimacy.

The shadow is uneasy too, he wishes he wasn't there either, this is too intimate, he feels like an elephant in a room, his presence should at least be acknowledged, yet it won't.

Elephant or shadow, he's following orders. He can't wait for this day to end, to stop being a shadow and be with his wife and kids, to forget about all this.

Elephant, shadow, or policeman.

The day ends soon, time to say goodbye already. Helene is hopeful that Paulin will be released soon, for good this time. Paulin is not as hopeful, this might be the last time he sees his family, and the only time he sees his daughter.

In the train, back to Aincourt, Paulin stares at the policeman, as if he was staring at his country. We lost the war, but we didn't have to bow to the enemy like that. Not like that.

Notes

Thank you for listening to the first episode of 31000/45000, the story of 2 trains of french members of the resistance.

Today, I talked about Paulin Coutelas, a man who lived in Rosny-Sous bois, a city close to Paris.

Paulin Coutelas was my grand uncle.

I just wanted to include here a little more informations about him.

First, my sources are the book Red triangles in Auschwitz , by Claudine Cardon hamet, the website Memoire Vive, and a conversation I had with Claudie Trocmet, the daughter of Helene and Paulin Coutelas.

Paulin Coutelas was indeed arrested on the 26th of October 1940 and stayed at the Aincourt center for some time.

The Aincourt internment camp was a sanitarium, converted by the french government on the 5th of October 1940, it was put in place in order to imprison members of the communist party.

When France was invaded by Germany, in June 1940, the french government was in peril and moved to Bordeaux, in the South, then in `Vichy. The president, Albert Lebrun, kept his position at first, yet the equivalent of the prime minister, Paul Reynaud, resigned and was replaced by Philippe Petain, who at the time was considered a hero of the First World war by the french population. He was the one who called for a cease fire, and would later create a new regime, the Vichy regime, replacing even Albert Lebrun. The country was then divided in 2 parts, both ruled by the Vichy regime, yet the North and west coast part was occupied by the german army, the south part wasn’t. This would change a couple of years later.

One of the consequences of the occupation was that France changed time, literally, and moved to the german hour, the Berlin time. So rather than being 4 pm, it was 5pm. The Berlin time is still nowadays in place in France.

Paulin Coutelas was indeed able to get out of the Aincourt center for one day, on the 28th of April 1941, and he met his daughter Claudie, who was a couple of months old at the time.

I don’t know precisely what happened that day, only that Paulin went back to his home to spend time with his family and was accompanied at all time by a french policeman. He might have been able to escape that day, yet made no attempt.

I wish to thank you for your attention