Illustration by Marion Lefebvre

Today is the 9th of May, Pierre Vendroux is back in France, in Chalon sur Saône, between Dijon and Lyon, south east of Paris, close to the swiss border.

He is exhausted, he is sick, but he is fortunate to find his family still alive, his wife Yvonne, his son Louis.

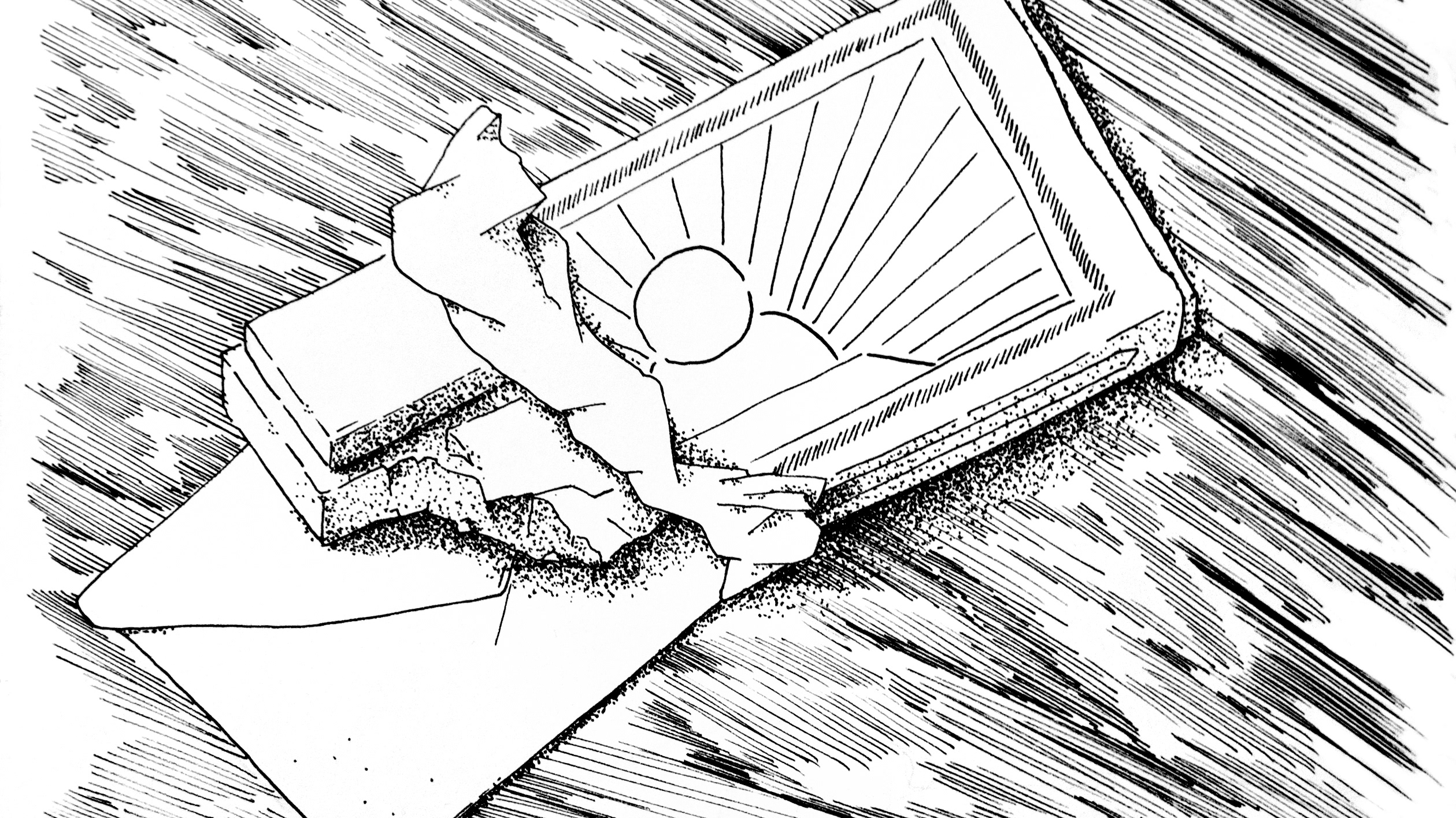

Pierre has something he needs to do, something that helped him survive in Auschwitz.

He gets a gun.

Back in 1942, Pierre was a tough man. He had been a soldier during the Levant campaign in Syria. Instead of a release for good behavior, which he didn't get, Pierre came back with his whole body covered in tattoos.

He was arrested on the 22nd of February 1942, as a hostage, after an armed action in Dijon. Indeed, he was part of one of the earliest resistance group, the Gloria network. Some say Pierre was the one who threw a grenade towards german soldiers on the rue de Bourgogne, in Dijon. He wasn’t thrilled to become a hostage, he was reassured his son Louis, a resistant as well, wasn't arrested with him.

But someone denounced Pierre Vendroux, he was sure of it.

He didn't know what to expect with deportation, but Pierre was willing to survive whatever the SS would throw at him. Already, he was looking forward to come back home, he made a special promise to himself.

Everyone had a strategy to survive, having a meaning, a goal, could mean a great deal. It could help you stay standing still during those exhausting roll calls, it could give you an extra reason to wake up in the morning, to stay alert enough to avoid a beating.

Pierre Vendroux had a goal, giving him a reason to survive, driving him to survive each day.

He also had his tattoos and quickly made use of it.

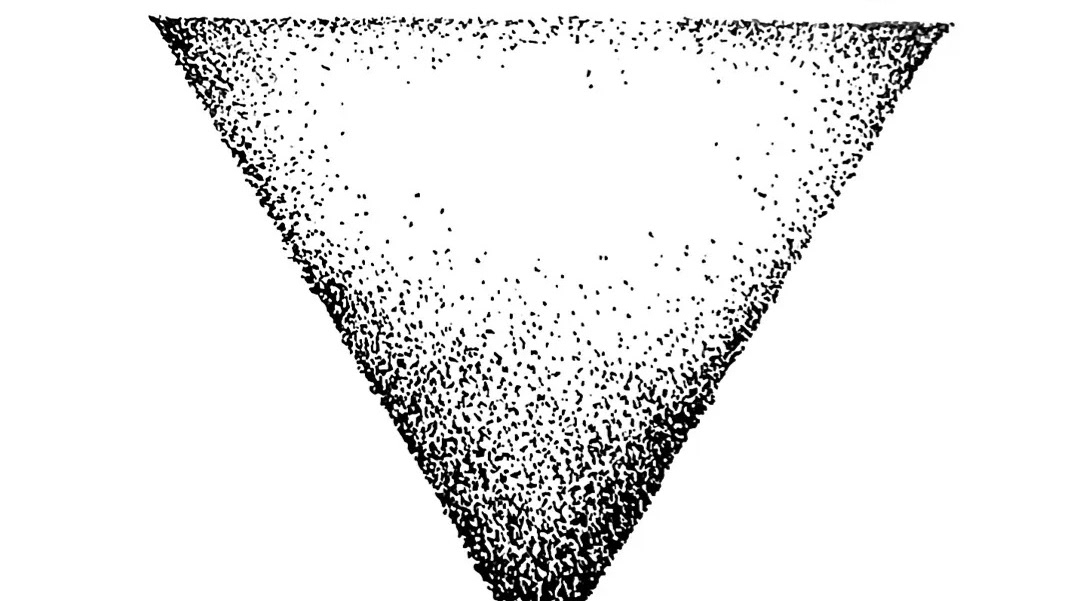

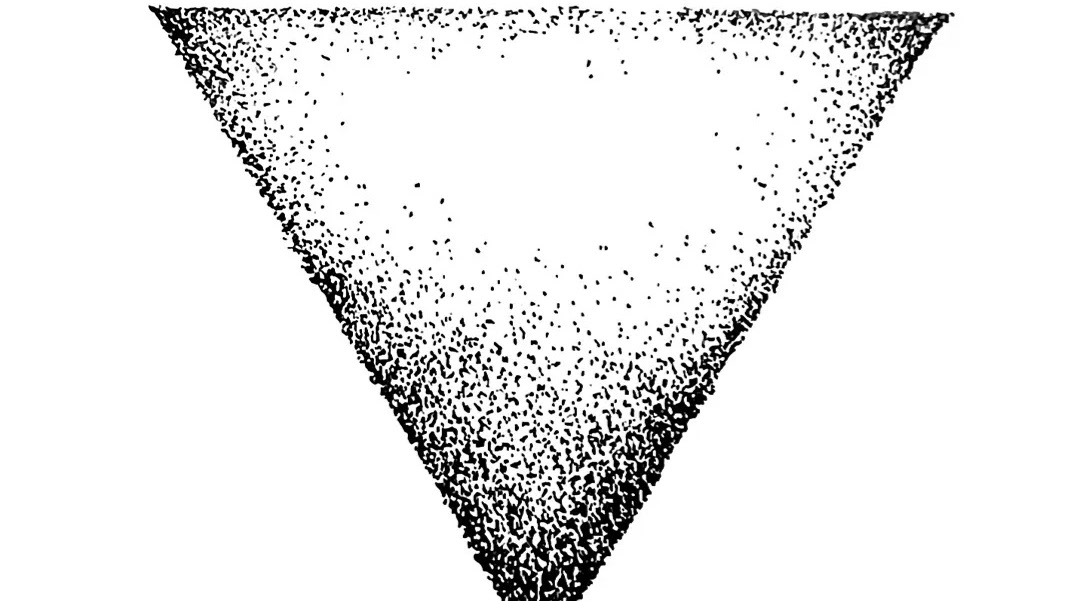

Pierre was affected to a difficult kommando in Birkenau, outside, under the scorching sun of summer 1942. Pierre looked around and noticed that all the guards and kapos around him were convicts, criminal prisoners. Because the 45000 were at first labelled as green triangles, criminal prisoners, instead of red triangle, Pierre saw an opportunity. So Pierre took his shirt off and showed his tattoos.

He made an impression instantly.

Not too many people had tattoos, it meant you were either a legionnaire, a marine, a criminal or a performer. It was a social marker, it meant you were part of a group who would protect you.

Pierre had so many tattoos it even covered the bottom of his legs. Each of them were telling a different story, either a war story, about the place where he was stationed, the men and women he met. He had tattoos of animals, women, knives stabbing hearts, 3 points, expressions, landscapes, and many more…

The guards and kapos were amazed, they would come to him, admire every inch of his body, listen to his stories. While he was doing that, Pierre couldn't work, he couldn't move. That was his intention, he would save himself, his energy, be protected.

No kapo wanted to beat Pierre, it would've been like ruining a beautiful painting.

When he received a new tattoo, a few months later, his own number, 46184, Pierre shrugged. One more tattoo, one more story to tell.

When the 45000 changed labels and became red triangles, it didn't change anything for Pierre, he was already a local celebrity.

Even if covered in tattoos and driven to survive, Pierre suffered, struggled, helped his friends amongst the 45000, resisted. He was then transferred to Flossenburg with 31 45000. Amongst them, Roger Debarre was still alive.

He was transferred once more to Dachau in November 1944. Then, he stayed, waited, saved his energy, convinced he would survive.

He did, he was freed on the 29th of April by the american army.

Back to the present, Pierre walks down a street in Chalon sur Saone. He will need to see a doctor, Pierre may have caught a number of diseases there.

But the doctor can wait, surely.

Pierre finds the man he is looking for. The man sees Pierre too, he recognises him, he knows he's back.

Pierre doesn't say a word and shoots him, the man falls but doesn't die. Pierre looks at him, he doesn't fire a second bullet. The man could have died, just like Pierre could have died in Birkenau, and this is all that matters.

Pierre promised himself to shoot the man who denounced him with one single bullet. This is all that drove him to survive, revenge. An eye for an eye.

The man looks at Pierre, not with anger or confusion. He looks at Pierre as if he was the one who was sorry for what happened.

Pierre won't do anything else to him, and he knows he wouldn't dare suing him. Revenge has happened, now it is time for everyone to heal.

It may be time for France to heal.

But how?

Notes

Thank you for listening to this episode of 31000/45000, the story of 2 trains of french members of the resistance. My name is Matthieu Landour Engel.

This episode was about Pierre Vendroux and his revenge.

Let me first give you a few informations regarding tattoos, back in the 40’s. Tattoos were not as common as nowadays (they are not that common nowadays, but they were even less in the 40’s.). They were a strong social marker. At first, tattoos were ornemental, they were a strong marker of a high class statut for some cultures, like egyptians, aborigens, papuans for example.

The process of tattooing may also have been used as a therapeutic technique in some cultures.

It was also used for darker purposes. Some cultures used it as a punishment and marked prisoners. Slaves were often tattooed so to indicate whom they belonged to. Soldiers sometimes were also tattooed in roman times.

Later on, with the discovery of indigenous cultures, european cultures stated to consider tattoos differently. First seamen and sailors came back from long trips with tattoos, which popularized tattoos. It stayed for a while a social marker for sailors, soldiers, prisoners, criminals.

In contemporary times, it became a fashion item, nowadays tattoos are less of a marginalised social marker, and more of a decorative procedure, which is not to say that it doesn't bear any meaning to those who have tattoos

The website memoire vive indicates that Pierre Vendroux may have something to do with the attack on the Dordogne street in Dijon, but it isn't 100% for sure.

Pierre Vendroux's revenge is an odd story, and so is the reaction of the man Pierre shot. It is strange, illegal, borderline absurd as the man didn't sue Pierre, but I believe it illustrates the strange times that post war France must have been. Resisters were walking free, alongside those that may have arrested them, or helped deport them, or helped execute some members of their families. There were trials, but some did their job, followed orders therefore it was difficult to sue someone who followed an order from a regime, the Vichy regime, which was declared non existent. Justice was made for some, it wasn't for other, some people like Pierre Vendroux decided to make justice themselves. This is a controversial decision from a controversial man.

I feel I need to add that Pierre Vendroux, according to Raymond Montegut's book, arbeit macht frei (page 336), had anti semitic opinions. Those were not as strong as the nazi's, yet I feel it is worth mentioning. One needs to remember that France, at the time, was a slightly anti semitic country. The Dreyfus affair is a strong example of the state of the opinion (even though it happened prior to the First and Second World War), I recommend anyone to read about this affair.

I have been trying to find Pierre Vendroux’s relatives, unfortunately, my research was unsuccessful. If by any chance, you know of someone related to him please let me know, I would be very pleased to get in touch and make sure the text I wrote doesn’t contain any errors.

My sources for this story mostly come from the book Red triangles in Auschwitz, by Claudine Cardon Hamet, the book "arbeit macht frei" by Raymond Montegut, le convoi du 24 janvier by Charlotte Delbo, the website politique-auschwitz.fr, memoire vive, the foundation for the memory of deportation website , the Maitron website, and the fantastic website auschwitz.org

Thank you very much for your attention, next episode will be about Fernand Devaux and Georges Dudal.