the card

Today is the 6th of August 1986, and Auguste Monjauvis receives a letter.

Back on the 17th of September 1941, Auguste was arrested by the police, as a member of the communist party. He was deemed a dangerous man, and the 18th of November 1939 decree made possible to arrest without trial any suspicious man. Nothing more, nothing less, that decree existed before the german occupation, before Vichy and Petain.

Auguste was indeed part of a triangle of resistance, distributing tracts all over the city, sabotaging the phones he was building for the german war effort. The police had no proof, Auguste was a discreet man, he made sure there would be no evidence.

But proof was not needed with the french laws and decrees in place. Suspicion was enough.

Auguste was sent to Auschwitz, he struggled with Raymond Montegut, they became close friends. He witnessed violence at its rawest, pure savagery, murder on an industrial level. To what end? What was the point of all this?

Auguste came back to France on the 7th of May 1945. He found his brother, he was arrested too during the war yet managed to escape. He fought until the liberation of France, De Gaulle made him a prefect.

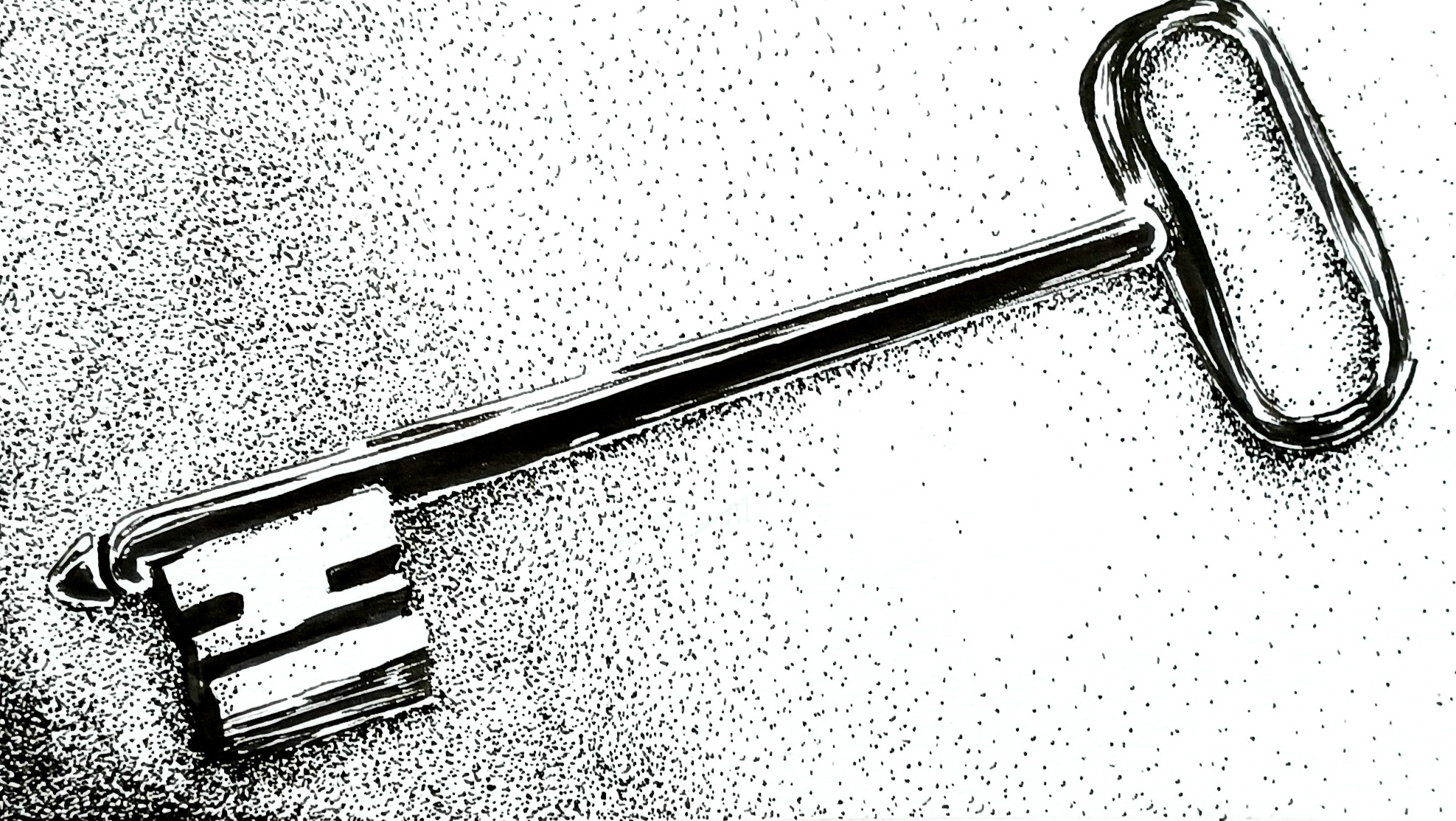

Victims of deportation could ask for a special status in post war France. You could ask for a political deported statut, which would give a pension of 5000 francs. Later on, in 1948, a new statut was created, deported resistant. The pension was better but it was harder to receive it.

Auguste asked for a deported resistant statut. But how could Auguste prove he was a member of the resistance? The government didn't need any proof to arrest him, but now they needed some. First he asked for the communists who knew him to sign a letter. This was of no help, communists were not allowed to get the deported resistant card. Communists couldn’t be members of the resistance apparently.

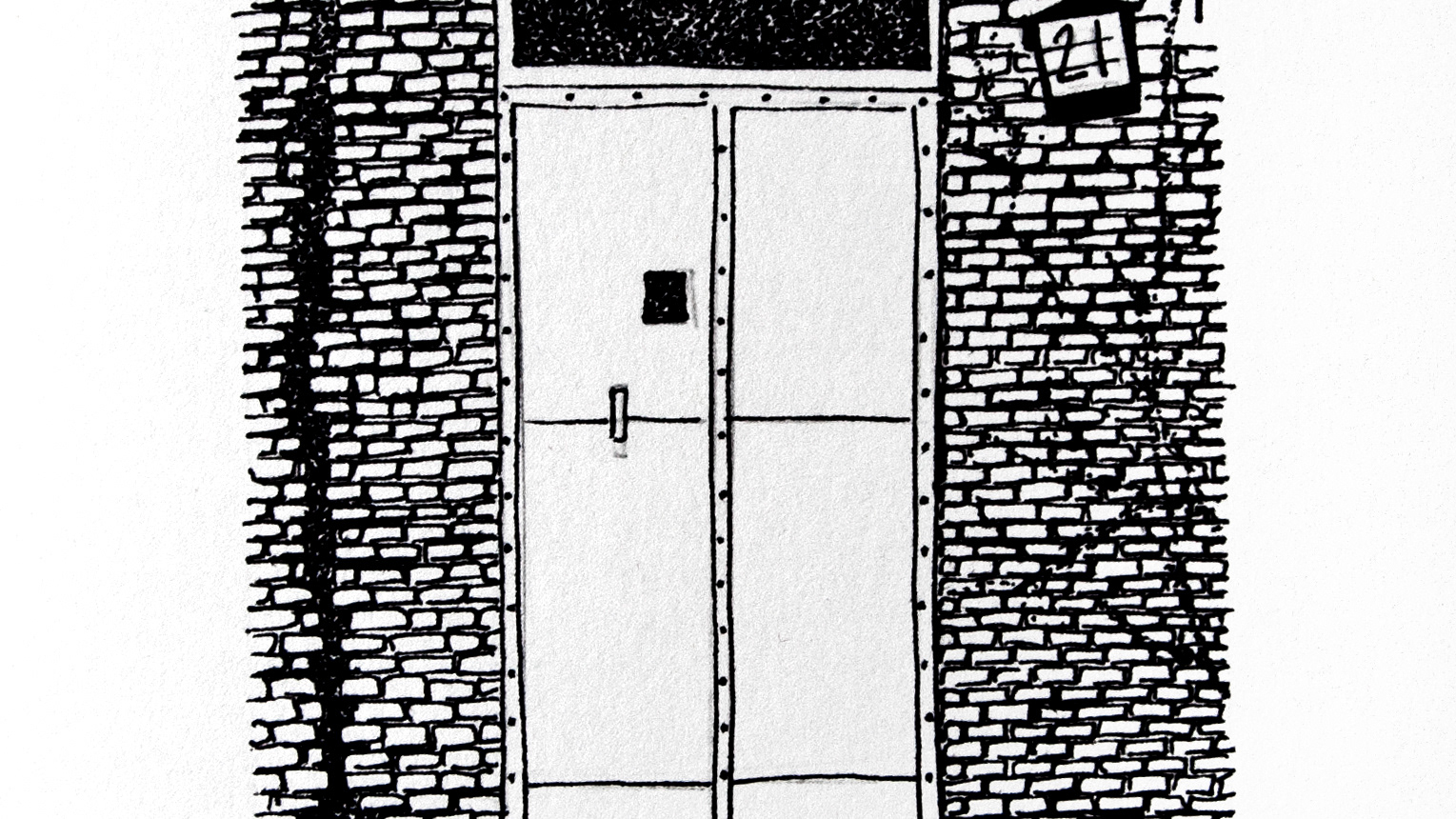

First refusal letter, the road to recognition was about to get much longer.

He knew some other people whom he sabotaged at a factory with. They were not part of the communist party, they wrote a letter to testify Auguste's participation to the sabotages.

On the 9th of October 1950, the administration sent him a second refusal letter. This time, Auguste was told there wasn't even any proof that he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, or anywhere. Now he had to prove he was deported on top of being a member of the resistance. Most of the records were destroyed, and Auguste's tattoo didn't seem to be proof enough. After all, anyone can get a tattoo.

All the things Auguste saw, all the friends he lost, and now he was being told that it didn't happen.

Auguste sent a third letter, after he got 2 more testimonies, from friends who resisted with him back in 1940 and 1941. 6 people in total, testifying personally that Auguste fought the germans.

This time, on the 29th of June 1953, the administration acknowledged that Auguste was deported, yet refused to see him as a member of the resistance. He should have been deported for a precise act of sabotage, not as a hostage.

Hostages don’t resist, apparently.

He filed an appeal, he lost once more.

His brother, recognised as a member of the resistance himself, helped, another appeal was made. Another refusal.

10 years passed, Auguste still couldn't let it go.

When some fought the french and german police in the last weeks of the war, Auguste and many others fought from the very beginning of the occupation. This had to mean something.

Time passed, memories faded with it, inexorably. Auguste didn't give up and kept researching. He received 3 new testimonies, sent a new appeal. But 2 dates seemed wrong, it was enough for the administration to send a new refusal letter on the 28th of February 1968.

11 people testified at the end. On the 21st of March 1986, Auguste was told that he would receive his deported resistant card. After all this time, it wasn't about the money, the pension, it was about acknowledging the past.

Back to the present, a letter comes. Auguste is 83 years old, it took 38 years but there it is, the deported resistant card. Auguste Monjauvis was a member of the resistance, from the early years of the german occupation to the dark times of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The shadow is lifted.

Notes

Thank you for listening to this episode of 31000/45000, the story of 2 trains of french members of the resistance. My name is Matthieu Landour Engel.

This episode was about Auguste Monjauvis and the 40 years it took him to be finally given a deported resistant card and pension.

I assumed that Auguste wanted this deported resistant card as a matter of principle, maybe he only did for monetary reasons, but given how many times he tried, I have a feeling this was really important to him.

Obtaining a deported card and pension was hard enough, as it could be difficult to prove a deportation. Many of the archives in Auschwitz Birkenau were destroyed, including the registration archives. Yet it wasn't impossible as the french archives were for the most part, still available.

Now a deported resistant card and pension was a much harder card to obtain. The police barely needed proof to arrest and deport, and the members of the resistance did their best to hide themselves and any evidence they were part of any network. Now after the war, those evidence were needed to get a deported resistant card, and those evidence were mostly destroyed, so proving anything was really hard. Plus being a member of the communist resistance was highly controversial. The resistance was supposed to follow the directives of De Gaulle and the french free forces, the communist resistance mostly followed the directives of the communist party, so you could on one hand argue that those are different types of resistance, but it was still resistance. The communist were among the first to resist in a country that, in its crushing majority, tolerated the collaboration implemented by the Vichy Regime. But the communists were controversial, their position regarding the pact of nonaggression between Germany and Soviet Union, even if many reacted to it differently, was still considered betrayal, many still loathed the communist, it is evident that denying the communists of that deported resistant card and pension was political.

The word resistance in itself was a controversial word. After De Gaulle and the French free forces liberated the country, De Gaulle and the government, for many different reasons, claimed that all its citizens resisted, in a way or another, that the country was a country of resistance. It is hard to agree with that point, yet this was the official version for decades, and it wasn't until the death of the general De Gaulle and the work of authors like Robert Paxton or documentaries like Marcels Ophuls " the sorrow and the pity" that it was acknowledged that, not everybody was a member of the resistance in France, and more those who were actual members of the resistance were still not recognised.

Auguste Monjauvis's case is the most extreme, many would have given up after a couple of tries, Auguste kept on demanding that card and pension for 40 years.

I have been trying to find Auguste Monjauvis’s relatives, unfortunately, my research was unsuccessful. If by any chance, you know of someone related to him please let me know, I would be very pleased to get in touch and make sure the text I wrote doesn’t contain any errors.

My sources for this story mostly come from the book Red triangles in Auschwitz, by Claudine Cardon Hamet, the book le syndrome de Vichy by Henry Rousso, le convoi du 24 janvier by Charlotte Delbo, the website deportes-politiques-auschwitz.fr, memoire vive, the foundation for the memory of deportation website , the Maitron website, and the fantastic website auschwitz.org

Thank you very much for your attention, this was my last episode. I hope you enjoyed listening to the story of those fantastic women and men.